Vertical Spread Parity: (Or why there's nothing special about credit vertical spreads)

One of the first spreading strategies normally taught to beginning options investors is the vertical spread. This is a spread between two calls (or two puts) with the same expiration date, but differing strike prices. The strategy gets its name from the fact that the prices for each leg of the spread are typically listed vertically, one above the other, on a traders screen.

It’s a basic option strategy, but it has many desirable qualities, not the least of which is a clear and easy to define risk/reward profile. It tends to be a popular strategy amongst options newsletters. Unfortunately, many newsletters seem to suggest only trading vertical spreads in certain ways, or seem to imply that certain vertical spread strategies are superior to others. The fact is that there’s no secret sauce. There’s nothing special about selling (credit) vertical spreads that makes it more profitable than buying (debit) vertical spreads. In fact, it can be easily shown that they’re effectively the same strategy.

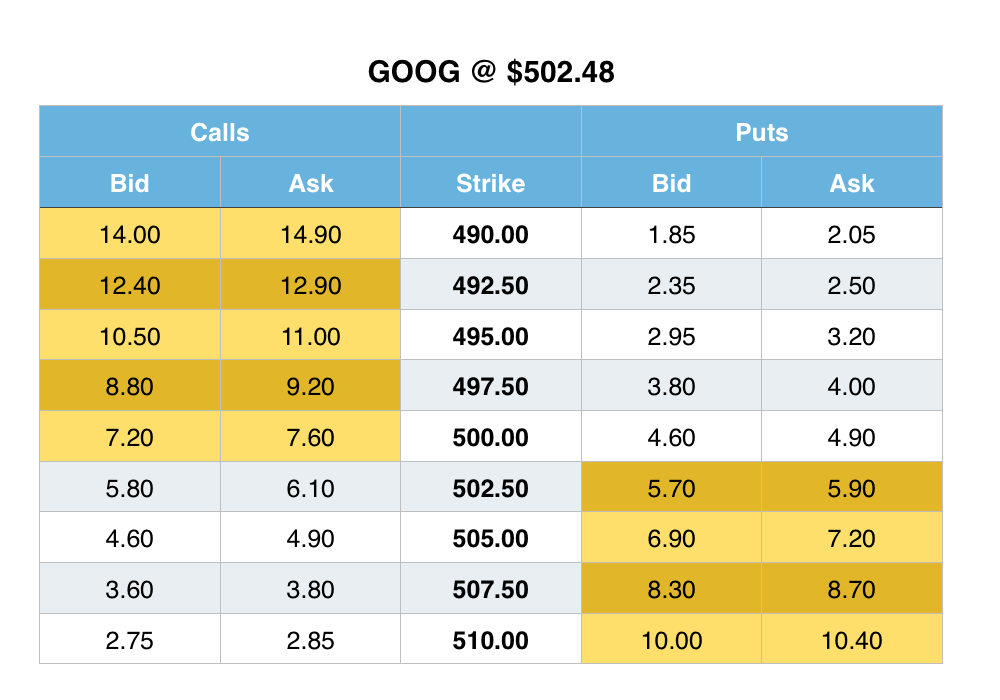

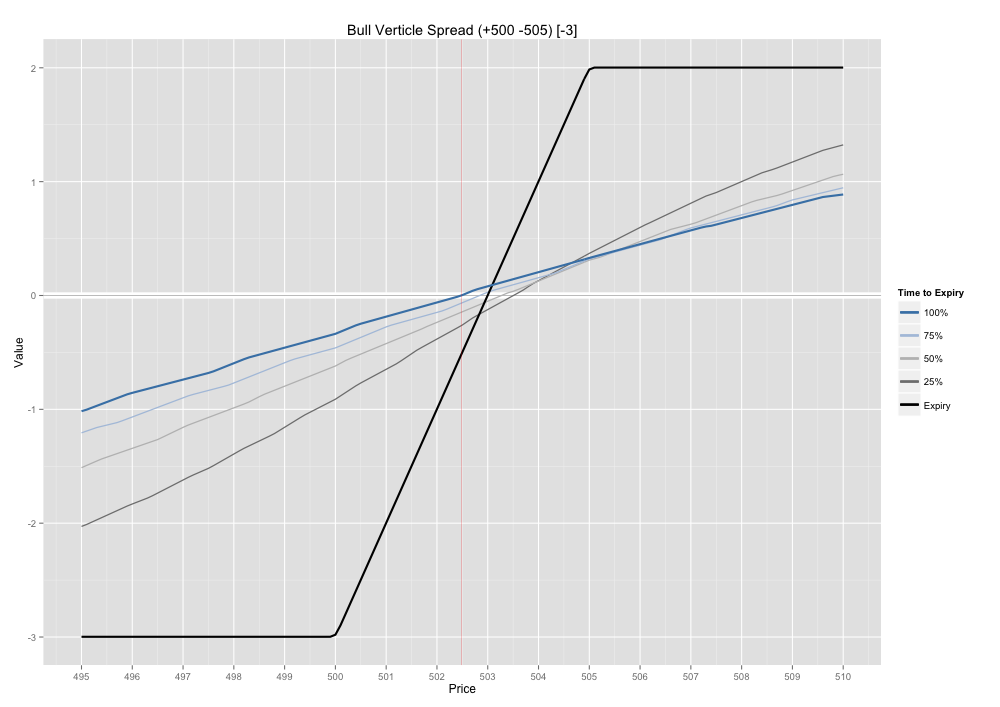

As an example, I will construct a simple “bull” vertical call spread in Google (GOOG), buying one of the 500 strike calls for $7.60, and selling one of the 505 strike calls for $4.60. An investor could purchase that spread for a net $3 debit. If the price of Google is less than $500 at expiration, the investor would lose the full $3 paid for the spread. If the price is greater than $505, the spread would be worth $5, the difference between the strike prices, and the investor would make a net of $2. Between $500 and $505, the value of the spread reflects the difference between the stock price and the $500 strike price. Therefore, a price of $503 at expiration would reflect the breakeven price for this investor’s particular trade.

For anyone familiar with vertical spreads, all of this is fairly straight forward. But the important thing to understand is that this exact same spread can be constructed using put options instead of call options. The savvy investor knows this, and would check both the call and put markets to see which spread offers the most advantageous pricing.

To construct the same spread as a “bull” vertical put spread, the investor would buy one of the 500 strike puts for $4.90, and sell one of the 505 strike puts for $6.90. That spread would be sold by the investor for a net $2 credit. In the case of the put spread, the investor is short the spread for $2, but the risk profile is exactly the same as being long the call spread for $3. In both cases, the investor loses $3 if the underlying is below $500, makes a net of $2 above $505, and the payout varies one-for-one between $500 and $505. The reason the relationship between these two spreads exists is due to “synthetics”.

“Synthetic” is simply the terminology used by options traders to describe the relationship, or the process of turning calls into puts and vice versa. This is based upon the fundamental relationship between call and put options and the notion of Put-Call parity. A call option can be turned into a put option simply by executing a particular trade in the underlying security. So too, a put option can be turned into a call option with a trade in the underlying security. The basic recipes for standardized options are:

1 long call + short 100 shares underlying = 1 long put

1 short call + long 100 shares underlying = 1 short put

1 long put + long 100 shares underlying = 1 long call

1 short put + short 100 shares underlying = 1 short call

Going back to the first example, the long 500 call option could be constructed synthetically by buying one 500 put and buying 100 shares of GOOG. The short 505 call option could be constructed synthetically by selling one 505 put and selling 100 shares of GOOG. The two trades in the underlying security exactly offset each other, resulting in no net trade in the underlying. There then should be little surprise when you realize that the net options position for this “synthetic spread” ends up being identical to the put spread from the second example.

In terms of pricing, the relationship is such that for a “5-point” vertical spread, a $3 debit on one side is equivalent to a $2 credit on the other side. For a “10-point” vertical spread, a $6.40 debit would be equivalent to a $3.60 credit on the other side. Going back to the prices for Google, the 495 / 505 call spread could be purchased for $6.40. As has already been established, this is equivalent to selling the 495 / 505 put spread for $3.60. But interestingly, the 495 / 505 put spread actually appears to be $3.70 bid. In this instance, the savvy investor would rather sell the put spread for a $3.70 credit than buy the call spread for $6.40 debit, because it’s a better price, for the exact same position. Interest rates and dividends must typically be considered with synthetics and put-call parity, but for this particular example, they can largely be ignored.

These basic synthetic relationships are areas where professional traders, and especially high frequency traders, excel. Yet the average options investor pays little to no attention to synthetic relationships. Take the time to check these synthetic spread relationships and always get the best price for your trades.